To Raze Everything in Life Down to the Very Bottom So as to Begin Again From the First Foundations

Author: Marc Bobro

Categories: Historical Philosophy, Epistemology, Metaphysics, Philosophy of Mind and Language, Philosophy of Religion

Word Count: 998

Listen hither

Editor's Note: This essay is the first in a two-office series on Descartes' Meditations. The 2nd essay is here.

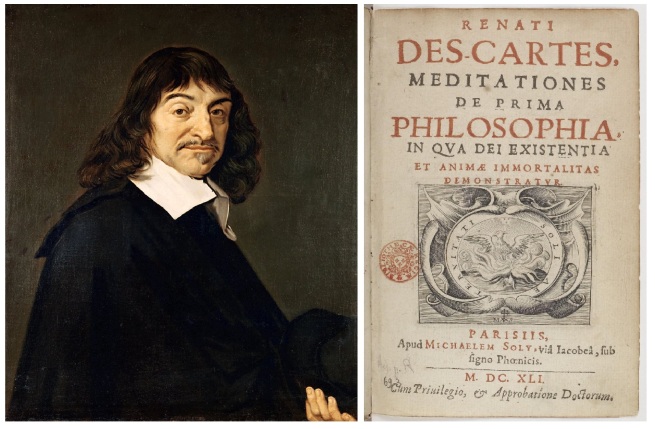

In an era of great debate over the fundamental facts of nature—e.k., about the Earth's place in the creation, the amount of free energy in the universe, the circulation of blood in the human trunk—René Descartes' (1596-1650) primal goal was to institute a body of scientific noesis that held the same caste of certainty as mathematical truths.[1]

The Meditations on Kickoff Philosophy (1641) is a classic work that lays the philosophical foundations of this enterprise.[two] Information technology raises timeless and fundamental philosophical questions near knowledge, the self, the mind and its relation to the trunk, substance, causality, perception, ideas, the existence of God, and more.

This 2-part essay reviews Descartes' process of reasoning and some of his arguments on these issues.

1. Meditation 1: Skepticism and the Method of Doubt

Descartes begins past reflecting on the unfortunate fact that he has had many false beliefs.[iii] He sets out to devise a strategy to not just prevent having false behavior simply, more dramatically, to ensure that scientific research reveals truth, not error.

To avoid any false behavior, his strategy is to uncertainty any belief he has that could be false or that he could be mistaken most.

His senses have deceived him before, so they could be deceiving him now, so he rejects all sensory-based beliefs. He reasons that if an alleged source of knowledge is sometimes deceptive, then information technology could always be deceptive, and and so it should exist rejected to find beliefs that cannot be false.

He realizes that if he were asleep and dreaming, many of his beliefs would be false: e.g., if he were dreaming almost walking somewhere, his belief that "he is walking," would be false. Since he cannot always tell if he is dreaming or not, this is further reason to doubt any beliefs from his senses: dreams appear the same as 18-carat experiences: they cannot be distinguished.[4]

He also realizes that he could be mistaken even almost beliefs that seem clearly true to him, whether awake or dreaming, eastward.g., that "bachelors are unmarried."[v] He could be mistaken, fifty-fifty about such beliefs, because he could be being deceived by some evil genius[vi] or even God: this is possible and he cannot show that it is not his actual situation. Since Descartes wishes to reject any belief that could be fake, that he could exist mistaken about, he rejects even these behavior.

The sciences, however, rely on behavior non but about the concrete earth merely likewise about mathematics, and by the end of Meditation 1, Descartes is tempted to rid himself of the want to acquire knowledge birthday.[vii]

ii. Meditation 2: The Essence of the Human being Listen

In an epistemological epiphany, Descartes notices that one of his beliefs cannot be doubted and is therefore certain:

"I am, I be, is necessarily truthful each time that I pronounce it, or that I mentally conceive it."

Descartes simply recognizes that he exists as long as he is thinking. This is true fifty-fifty when he'south dreaming and even if he were deceived past an evil demon or even God. Whenever at that place are thoughts, those thoughts (and their thinker) be, even if those thoughts are inside a deception. This is the Cogito as information technology is given in the Meditations.[8]

So, Descartes knows that he exists, but what kind of a thing is he? He can conceive of himself existing without a body, just cannot conceive of himself existing without thought. So, he must be a thinking thing: something doubting, understanding, affirming, denying, willing, imagining and feeling. Descartes takes this to hateful that he is essentially a mind and non a trunk.[9]

How does the Cogito escape the internet of incertitude cast in Meditation ane? Descartes says that judgments about his own thoughts are entirely unproblematic; the contents of his mental states are clear to him, meaning that he can clearly tell what his ain beliefs are. Withal, even granted this "transparency" of mental states, how does he know that there is a unmarried entity that is the field of study of all of his thoughts? Descartes asks rhetorically, "Am I non the aforementioned who now doubts about everything, who still understands something; who affirms that this one thing is truthful?" His unstated answer is that he is a single entity that endures over time.[10]

iii. Meditation 3: The Existence of God

Existence a thinking thing, Descartes knows that he has ideas. He notices that one of these ideas is the idea of God, i.e., something eternal, space, all-knowing, all-powerful, all-skilful, and the creator of all things. But where did he get this idea of God, a perfect beingness? Did he invent it? Did information technology come up from other people? No. His thought of God could just take come from God. Co-ordinate to Descartes, a cause must be at least as existent or perfect every bit its effect. The thought of God notwithstanding represents much more reality and perfection than the idea of himself, or of annihilation else.[eleven] There's just and so one possible cause: God. So, God exists. This is Descartes' causal argument for God's existence.

However, God might be a deceiver: God could have fabricated Descartes have many fake beliefs. That'southward possible. How then can Descartes be sure that he can trust whatever of his other beliefs too the belief of his own existence? In the case of the Cogito, Descartes saw very "clearly and distinctly" that to retrieve, 1 must exist. But how does he know that clear and distinct perception is always reliable?[12] East.g., how does he know that "triangles take 3 sides" if there's an evil demon deceiving him?

He at present realizes that in that location is no manner that an all-proficient existence[xiii] would make it and so that when he "conspicuously and distinctly" thinks something to be true that information technology wouldn't be true: an all-good being would not deceive him or permit an evil demon such license. Plus, he's but proven that God exists. Then now he tin trust that whenever he "clearly and distinctly" thinks something to exist truthful, it is.[14]

This essay is the beginning in a two-office series on Descartes' Meditations. The second essay, Meditations 4-6, is here.

Notes

[1] For Descartes, knowledge of the sort that can serve every bit a foundation for science requires certainty, which in turn requires indubitability, namely, that information technology tin't exist rationally doubted. This is a very high standard for knowledge, and of import to understand because it's straight relevant to responses to Cartesian skepticism that deny the indubitability requirement.

[2] Many of Descartes' other works, such as The World, Treatise on Man, Description of the Human Body, and Optics, focused on providing the scientific content itself. See Descartes: The World and Other Writings , ed. Stephen Gaukroger (Cambridge, 1998).

[iii] "Several years have now passed since I offset realized how numerous were the false opinions that in my youth I had taken to be true, and thus how doubtful were all those that I had subsequently built upon them. And thus I realized that once in my life I had to raze everything to the ground and brainstorm again from the original foundations, if I wanted to establish annihilation firm and lasting in the sciences" (Med. one). Descartes was in his mid-30s by this bespeak.

[4] "I meet so apparently that in that location are no definitive signs by which to distinguish being awake from existence comatose" (Med. 1).

[5] "Whether I am awake or comatose, two and three added together are 5, and a square has no more than than four sides" (Med. 1). Such behavior are typically called analytic a priori, since they are non based in sense-experience, and can be known purely by definition or reason.

[vi] Sometimes translated as "malicious demon." The Latin is genium malignum. I prefer "genius" to "demon," since the latter has a religious connotation, merely at this point in the Meditations religious belief of any kind is still in doubt.

[7] "I am not unlike a prisoner who enjoyed an imaginary liberty during his sleep, but, when he later begins to suspect that he is dreaming, fears being awakened and nonchalantly conspires with these pleasant illusions" (Med. 1).

[viii] Interestingly, the famous inference cogito ergo sum ("I think therefore I am") occurs in Descartes' Discourse on the Method (Function 4) and thePrinciples of Philosophy (I.7), but non so in the Meditations. It'due south not clear why Descartes doesn't exercise then in the Meditations. Some commentators debate that given his method of dubiousness in the Meditations, even simple inferences are put in question. That is, at this stage of the work, Descartes is not fifty-fifty certain that logic is reliable, and so cannot legitimately argue from premises to a decision that he exists. Another style to explain the absence of the ergo is to signal out that Descartes is seeking a foundational conventionalities upon which to justify all of his other behavior and therefore ground knowledge, and that for a belief to be properly foundational it must non stand in demand of justification itself.

[nine] To say that he is essentially a mind and non a body is to say that his mind is function of his essence: if his mind ceased to exist, he would terminate to exist, merely he could exist without his body, so information technology is not part of his essence. Descartes too argues in Med. 2 that his knowledge of his mind through non-sensory means is too the best way to know his trunk. To bear witness this, he uses the case of a piece of wax. Even when its sensory backdrop change (through melting, hardening, changing color, etc.) it remains the same piece of wax. So, the wax itself cannot be known through the senses. Also, the truthful essence of the wax is known through the senses, for the wax can take on a keen, perhaps infinite, variety of shapes.

[10] As for his reasoning, Descartes is probably appealing to the fact that he experiences himself every bit a single entity through time. Immanuel Kant will famously claiming this line of reasoning in the Paralogisms of Pure Reason in his Critique of Pure Reason (1781).

[11] According to Descartes, each thing is "assigned" a degree of reality (which corresponds to its perfection, that is, its capacity to be independently). In other words, everything has a place on the hierarchy of reality. God, of class, is at the "top," since he is the most perfect, most independent being possible, and then has the greatest degree of reality.

[12] He asks: "What is required for knowledge is my simply having a clear and singled-out perception of what I am asserting. Surely it'due south non possible that I could have a clear and singled-out perception of the truth of some judgment (proffer) which turned out to be false?" (Med. iii). For this reason, Descartes is often chosen a "rationalist," since clear and distinct perception, upon which all knowledge ultimately rests on, is not a course of sense-experience.

[xiii] Descartes defines God as all-good. But in Meditation 1, he mentions that being "all-skillful" doesn't automatically rule out some deception on God's part. Even the Bible seems to depict God as a begetter who lets his children (united states) exist deceived sometimes. If God allows united states to be deceived sometimes, why couldn't he permit us to be deceived all of the fourth dimension? Only at this point in Meditation 3, he realizes that such a worry was overblown, for he now clearly and distinctly perceives that God would not allow u.s. to be deceived in such a sweeping mode.

[fourteen] We tin can at present see the so-called "Cartesian Circumvolve." Descartes wants to remove the possibility that there can be a deceiving God or an evil demon deceiving him. To do this, he first argues that God exists and 2nd claims that God couldn't be a deceiver. At present to prove that God exists he says that he clearly and distinctly perceives a causal principle (that there is every bit much actual reality in a crusade as there is representative reality in its outcome). And to testify that God is non a deceiver he says that he clearly and distinctly perceives that deception is incompatible with perfection. But retrieve why Descartes is trying to show that God couldn't be a deceiver: in order to validate his provisional full general rule that he can trust clear and distinct perception! See the circle?

References

Cottingham, John, Robert Stoothoff, and Dugald Murdoch. Eds. and trans. The Philosophical Writings of Descartes (Cambridge University Press, 1984), vol. 2.

Francks, Richard. Descartes' Meditations: A Reader's Guide (New York: Continuum, 2008).

Gaukroger, Stephen. Ed. and trans. Descartes: The Globe and Other Writings (Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Wilson, Margaret. Descartes (London: Routledge, 1978).

PDF Download

Meditations 1-3 in PDF; Meditations 1-6 in PDF.

Audio Recording

Besides in mp3 sound download.

Related Entries

Descartes' "I retrieve, therefore I am" by Charles Miceli

Epistemology, or Theory of Knowledge by Thomas Metcalf

al-Ghazālī's Dream Argument for Skepticism past John Ramsey

External World Skepticism by Andrew Chapman

Moore's Proof of an External Globe: Responding to External Globe Skepticism by Chris Ranalli

Modal Epistemology: Noesis of Possibility & Necessity by Bob Fischer

Philosophy and Its Contrast with Science by Thomas Metcalf

Most the Author

Marc Bobro is Professor and Chair of Philosophy at Santa Barbara Metropolis Higher in California. He holds a PhD in philosophy from the University of Washington, Seattle, an MA in philosophy from King's College London, and a BA in philosophy from the University of Arizona, Tucson. He specializes in the history of modern philosophy, specially Leibniz. Bobro is likewise the bassist and tubist for the mythopoetic punk band Crying four Kafka and collaborates on art with Elizabeth Folk. https://marcbobro.academia.edu

Follow 1000-Discussion Philosophy on Facebook and Twitter and subscribe to receive e-mail notice of new essays at the bottom of 1000WordPhilosophy.com

Source: https://1000wordphilosophy.com/2018/08/04/descartes-meditations-1-3/

0 Response to "To Raze Everything in Life Down to the Very Bottom So as to Begin Again From the First Foundations"

Post a Comment